A stone’s throw from the Central Business District (CBD) of Cape Town, South Africa, sits the studio of artist Tafadzwa Tega. The nearby streets hum with the sounds of people going about their days, quieter now than before the pandemic. Whether they’re selling vegetables or clothes, walking their dogs, or on a lunch break, Tafadzwa picks up on the different languages they use and initiates conversation. It is in this environment that he finds stories similar to his own.

Born into a family of artists in Zimbabwe, Tafadzwa found second homes in his uncle’s and brother’s art studios from the time he began helping out at eleven years old. But following his graduation from art school years later, Tafadzwa felt compelled to move to South Africa with the hope of having access to more opportunities.

Nearly thirteen years on now and Tafadzwa has found his stride in depicting other immigrants. He celebrates their emotional and physical journeys of loss and hope, honoring them and those like them worldwide. And, after a brief battle with Covid-19 earlier this year, he’s hungry to spread his message as far as possible.

Kinship + Craft spoke with Tafadzwa Tega over Zoom for this interview. It has been edited for length and clarity in collaboration with him.

A family of artists

K+C — Hi Tafadzwa, thank you again for talking to me about your work! I’m really excited to get started.

It’s a pleasure.

K+C — I wanted to begin with how you would describe yourself and what you do. Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

For me, I was born in an artistic family. So, I started doing art at a young age, like 10 years old. I was already attracted to art and my family could already see that I was into art. Even at school, the teachers, they already saw that I was into art, so they started to support me. But after high school, that’s when I went to art school.

I challenged myself because most of my family are also artists, like sculptors. They were doing metal sculptures and other stuff, so I challenged myself to go and start painting. I wanted to become a painter and do something different than anyone else.

K+C — Your uncle and your are also both artists. Is that right?

Yeah, yeah. My brother is an artist. He’s a full-time sculptor. He’s in Denmark now.

But at the time he was busy doing some work. Sometimes he needed an assistant in the studio, so I would always go and help him cut some metal, join everything, and prepare things for him on the school holidays.

K+C — What was it like having other artists in your family?

I think, for me, it was everything I needed. Even if I needed some good sneakers my brother would say if you want something you must come and work for it. So, for me, it was a job at first, and then I started enjoying it. Plus, I was also getting nice money from my brother, so it was cool, man. It was cool to see everyone.

I was talking to my friend last time — I said, “The time I was growing up, I never saw anyone in my family go to work. People, they just woke up and went to the studio. Everyone was busy with his own stuff, assignments and all this stuff,” so I was just laughing about that in my family. I never saw people go to work a nine to five.

K+C — Was it really normal for you to be in the art studio, in general?

Yeah, it was, yeah. After school, I was not with my friends or hanging out. I got changed and went straight to the studio. So it was cool, man. I’m like a young boy and I’m hearing this cool stuff [being with my brother] and then when [he and his friends] went out, they came back and I heard the stories and all this stuff. I miss those days.

K+C — I can imagine. It sounds like an amazing experience to have had, and very inspiring to be around. It seems like an extension of your home life in a way.

It is. It is definitely part of me.

A new start in South Africa

K+C — You moved from Zimbabwe to South Africa approximately thirteen years ago. Could you tell us about that experience?

Yeah, so, what happened is, after I graduated from art school, I was thinking about how things were getting bad in Zimbabwe. The smaller places were closing — like a lot of places that were [part of the art community] — they were closing. So when people wanted to do exhibitions or show their art, they tried to come to South Africa instead. And, my auntie was already staying here, so I thought, “Hey, let me make a trip and see how things go.” For me, I was challenging myself. I was in two totally different countries, and they do totally different stuff.

I moved to Cape Town in September 2008. When I got here, I was seeing bigger stuff — bigger places, opportunities. It was not easy the first time. I was still a new guy and what I knew back home was not the same, so I started from scratch. Building my name, looking for a studio, and meeting other friends, also from Zimbabwe — people I knew.

K+C — Oh, nice. So you knew a couple of people already?

A couple of people. So, I started asking questions; they started helping me. We did it like this and that’s how I grew. That’s where I came from, and it was not an easy road.

There was a collective I joined in 2008 called Good Hope Art Studios in Cape Town. So after that, I started planning my first solo show. It was in 2012, at AVA Gallery, also in Cape Town. I think, after my solo show, I saw many people getting drawn to the work and people wanted to hear my stories. I met some collectors and started participating in the art community. The rest is history, but yeah, it just slowly built up.

It was not in one day. It took time — months. You’re asking yourself, “When is it gonna be the day that I’m gonna be at this stage, or that?” But I realized I was like a child. When I started, it was like a child starting to crawl, and then walk, and then balance, and then walk, and then run.

K+C — What were the specific challenges you faced when you first got to South Africa besides finding a studio space and getting accustomed to the new place?

I think that the first challenges I had were how to work with a gallery and how to be accepted by the community. Where I come from, I come from a community, [and] I was so close to my community. I could do whatever I wanted in those areas. So, when everything was limited, I had to control myself. I had to know what time to be at this place, and why I was at this place, right? It was that kind of scenario.

The first time, you’re a stranger to the community. But that was so tough for me. When you are someone who does creative work, you need peace of mind. You need to relax; you need to be in a good space to produce some good quality works of art. It was so difficult at the beginning. I was supposed to pay rent and make a living; I was supposed to send money home. So it was not easy.

K+C — Mhmm.

I think, for me, it was easy for me to mix with some local guys. So the guys from Zimbabwe, who helped me, I would meet others through them and I also engaged with the local guys too, like, to see the movement. I also got a job as an assistant for other artists. I think that’s the way I got in the game. I was seeing every movement they make and I was also a hard worker, so I was pushing myself. The guys would also see that, and they were helping me to crossover.

[For example,] I didn’t know where to take my work, or which color was gonna suit me. So, every time people came to see other artists, well, it was an open space where a lot of artists were working, [so they saw mine, too]. Other people saw the work and visualized the work — they always asked.K+C — That’s fantastic.

It was not in one day. It took time — months. You’re asking yourself, “When is it gonna be the day that I’m gonna be at this stage, or that?” But I realized I was like a child. When I started, it was like a child starting to crawl, and then walk, and then balance, and then walk, and then run.

K+C — So, you were all working in this one big space and when people visited another artist, they would also see all the others, and that helped you make connections?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think also that art is about connection, as well. You have to know people in the game. If you don’t know anything, you don’t know what’s going on — maybe there’s a call out, they need artists, or there’s a group show — you must know people who know people.

But, nowadays, there’s Instagram, so it’s very easy for people to connect. When we started, though, there was no Instagram. It was email, so people had to know people. You had to know curators. But now, these curators go on Instagram to check the artists they want.

One thing to add is that you can’t approach people; they must approach you. So that’s how difficult art is. You must know people; they must come to you and say we like your work. You might want to work with them, but you can’t go to them. They’re going to say, “No, we’re not interested,” and it’s going to be heartbreaking.

K+C — It’s that discovery element, right? Many people take a lot of pride in it, or maybe it’s an ownership thing, but there’s this — I’ve discovered this person — mindset.

Yeah, yeah.

Sharing the stories of immigrants

K+C — Speaking of connecting…A lot of your paintings depict people, from those alone in interior settings or in small or large groups. How much have the people around you in Cape Town influenced the creation of those in your paintings?

So, when things were tough in Zimbabwe, people tried to come and buy some stuff from South Africa. There were these good relationships with South Africans. The first time, it was difficult for Zimbabweans to come to South Africa, but South Africa could see the hunger in Zimbabwe, so they opened the borders for the people. They removed the visa [requirement], so a lot of people came here to look for greener [pastures].

There are people I know from back home [in Zimbabwe] who moved to [South Africa], and I know their qualifications. They’re doctors, teachers, professors, even business people. But, they dropped their stuff to come and start [a new life]. So, when I see them here, like looking for jobs, or a doctor working in a restaurant because they’re looking [to make] ends meet, I’m so touched. Those people, I know them and I’m so close to them. So, that’s who I put in my paintings. They are the people I portray in my paintings. If you see some of my previous work, like a massive group of people, they are a lot of Zimbabwean people. They used to go and apply for asylum.

K+C — I see.

Things were bad in Zimbabwe. People wanted to stay, but they were leaving instead. So, asylum seekers — there could be 100 people, [but the government] would tell you [they’re only] going to take 20 [people] a day. But, before they give you asylum, they must interview you, right? So, people would go and would fight each other, or pressure each other, just to get inside [the consulate for an appointment].

It was so touching for me, that this was happening to my people. But, the way they had been treated, and the hunger for them — they wanted to stay, but things were not okay for them to stay. [And,] things are not okay for them to go home, right? So there’s no other way. There’s no way you can survive, so you fight for your life. So, for me, when I sit down, when I see an empty canvas, those are the stories I wanna portray in my work. I want to say to people — like a journalist wants to put a story in the newspaper — I want to explain to people what is going on.

K+C — That reminds me of one of your paintings with around 20 or so people. Does that connect to this asylum-seeking space or are they dancing?

So, the story for that painting is so funny. Yeah, I was just taking a walk, and one of my cousins phoned me and said, “Did you hear what happened?” I said, “No, what’s going on?” He said, “Our former President Robert [Mugabe] has been taken away. They’ve been cooked.” So, for that moment, just to hear the news from every Zimbabwean — it didn’t matter, wherever you were, it was a joyous celebration. Even other people, who weren’t Zimbabwean, they were happy for us. Everyone was happy.

At home, people, they didn’t sleep that day, after hearing the news that this happened. It’s like people there, they promised that everyone was going to get a million dollars. It was the joy of every Zimbabwean and my phone was buzzing in. So, I was calling back home, and talking to another friend of mine, who was saying [that] people are gathering. They were sitting at this place, people there, drinking, partying. It was like our independence. So, when I got back home I was just thinking of that. I was thinking of the canvas and picturing people.

People, they’re helping every year. Your family is calling; they’re happy. You’re going to picture their house. In your mind, you are there already, but you’re not there. So, I created a picture [in my mind, and] then put it on the canvas.

By the way, it was successful. I think that painting was almost six and a half years ago. I enjoyed doing that painting. Then I got the opportunity to do a solo show by Gallery Momo in Cape Town. After that the painting sold, but, yeah, I love that work. I think I’m going to buy it back in the future.

K+C — I hope you can get it back! It sounds like that painting represented such a big moment and, in a way, it connects all the different stories of the people you paint.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, if you go on Youtube and just search that story, you’ll see our people. They were happy and rejoicing. At last, this thing happened. People were wishing that he would step down, and at last, he did step down. Then the whole town was shut down. People were happy. The soldiers [and the] people united, but only that day. Everyone was united on that day.

Yeah, so, it means a lot for me, and also for the Zimbabwean people.

K+C — And for the more intimate portraits that you do, are the people in those paintings fictional, made up of a collection of different stories you created? Or do you base them on people that you’ve met in real life?

Yeah, so where I stay in Cape Town is not that far from the CBD, and my studio it’s close to the CBD. So, when I take a walk on the main road, I always see vendors — people selling and people looking for jobs. I think everything’s here. Cape Town is a harbor city for all Africans because you can see people from Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.

I’m Shona, so I can hear people speak my language from far away. So, I go there — maybe they’re selling something, vegetables in the streets, but I go there and talk to them and hear their stories. Even if I see someone walking or taking a dog for a walk, I want to have this conversation. Like, why are you doing this? Where are you from? What is the story? Why are you here? And, also, we have a group of Zimbabwean people, so we help the people who are looking for jobs.

For me, it’s easy to interact with them. When I interact with them I get that opportunity to ask them, then I can tell them my story. [I ask, if they] can come to my studio, then I take their pictures. Or some of them dress nicely on Sundays. They’re going to church, so they send me pictures they enjoy. That’s the kind of movement I end up doing. I do a painting for them and it’s like the story keeps on, like starting to give birth to another story.

Representations of culture, education, and memory

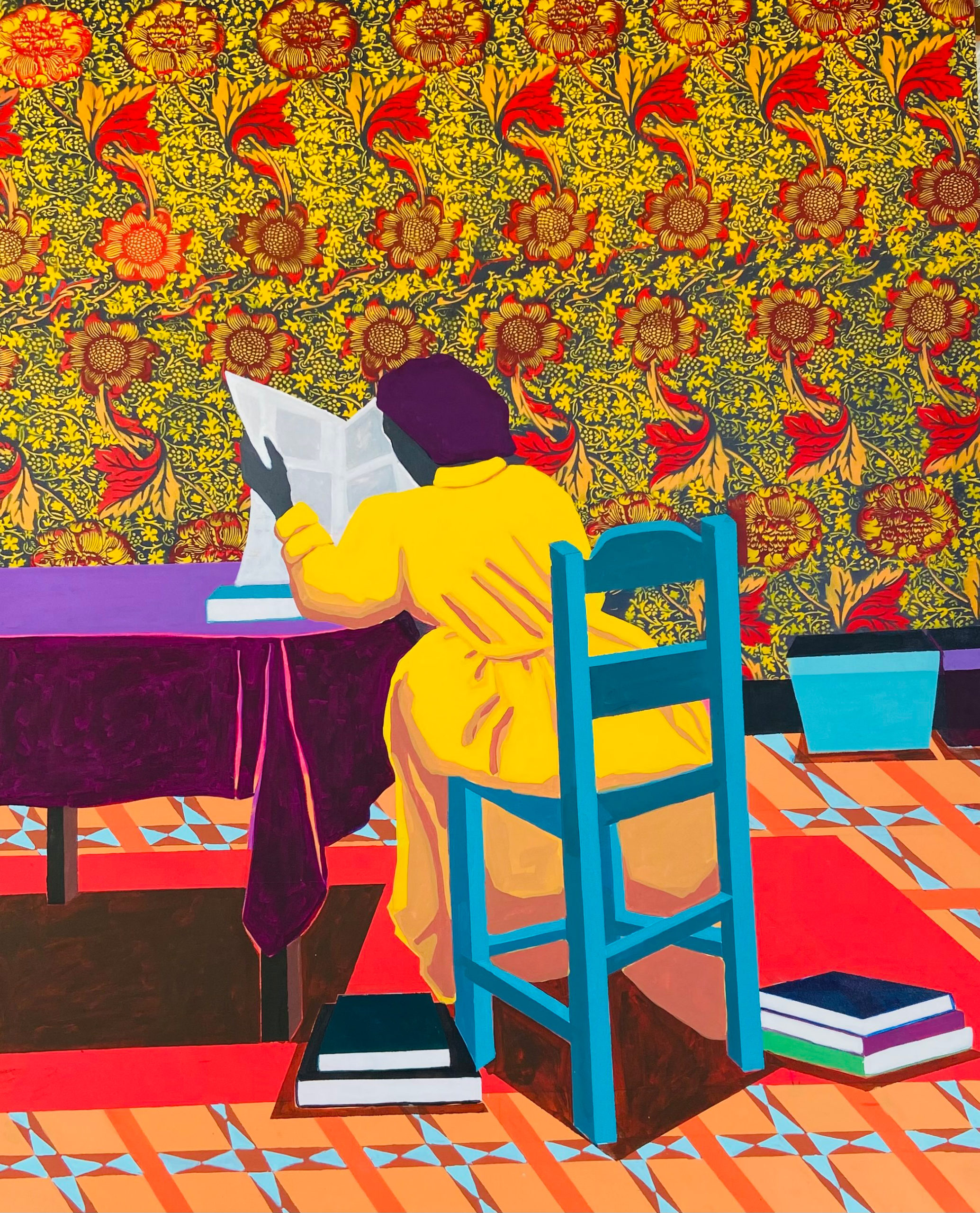

K+C — That’s wonderful. Now, what about the interior scenes with different colors, patterns, and objects? What roles do these play in the overall composition?

Okay, nice. Good question. So I don’t know if you have checked on my recent work — there are some books.

K+C — Right, stacked up, for example.

Yeah, there are these books lying all over the paintings. So, if I can, I start with the books. I think 95 percent of Zimbabwean people are super educated, like, properly educated. But, they are so down. They are doing everything to make ends meet [and] to survive.

Then, when it comes to the plants, there’s this plant in Zimbabwe that my grandmothers believed in — it’s like this type of coffee. People drink it or something. So, when someone’s daughter gets married, the mother goes to the backyard and digs up that plant, or they put it in a tin. They say to take this plant and plant it in your yard. It’s gonna protect you when your child gets sick. So, they believe the plants look after the people, and that they chase the bad spirits.

So, when people build their houses, they put in hedges and they grow this plant. It has a nice huge flower in Christmas-time, so people stand [in front of it] and get pictures. In my paintings, people are standing in front of those flowers. For me, if I think about home, those flowers are the first thing that comes to me.

K+C — Okay. So it’s not just a protective symbol, Zimbabwean grandmothers also use it for health reasons, too?

Yeah, as a visual [protective symbol], but it’s also addictive.

K+C — How do you decide which background patterns to use?

You know, to be honest, I don’t plan these things. When I look at the canvas or when I start painting, I can see the color that dominates and I go with that color. It just comes naturally. The color that [I start with is in] the figure is in the flow, so the colors which I put on the floor, if they dominate, that’s the color used in the background.

K+C — And do the colors have anything to do with the stories themselves?

I think, we Zimbabweans, we are full of colors and colors are big back home. One of my uncles used to dress up in those 90s clothes that block colors. You can see someone from far away when they’re coming [in those clothes] — like, oh, this is so-and-so. They’re those kinds of people. That’s where I get all of those colors. When I think about those days, [I think of] the 90s people making something graphic, something colorful. So, that’s what the colors remind me of. They don’t have any meaning, I think. There’s that freshness.

I still have those older pictures from before, so when I put the colors on the canvas sometimes I laugh. I have that connection. I still remember this Christmas, and this and this. They just bring back good memories and they give me good memories.

K+C — That’s wonderful!

Yeah, so I think in my work, most of the time, I go back to my childhood and what was going on then. [For] most of my paintings, it’s when I was growing up — my childhood and my teenage days.

K+C — Okay. I’d like to ask one more question about the interiors that you use. Sometimes there is a lack of interior objects, for example, the dancing scene was more focused on the people and their movements. However, in your more recent paintings, you have filled the interiors with more, from books to house plants, furniture and patterned wallpaper. How do you decide when to use these visual devices and when not to?

So each and every painting, when I sketch it or when I try to curate it, it always brings me stories. Every painting always [tells me to] keep going or to stop. That is it, I don’t decide. I think when I engage with the painting it will tell me, “No, this is done now.”

[For example, the painting will tell me], “You’re going to overwork it,” or “You’re going to remove the message now if you keep working on this.” Sometimes you want to work more, but the painting says, “No, no, no. This is done. This is done.” But then, the other people like they want some objects. They want some things. They engage with everything you put in, so you can enjoy the process.Also, they said a painting is never finished. You could keep working on one painting for years and years and years.

K+C — So it’s an intuitive process?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s kind of like how [to decide] whether the storyline is finished or not.

Tafadzwa Tega is ready for what’s to come

K+C — I understand. And there’s a new series that you’re working on right now, correct?

Yeah, yeah. I’ve got a new series of work which is coming soon. I’m talking to this gallery in Italy, in Milan. Yeah, yeah. We’re going to plan some shows. I think we’re going to have one show in Miami in December. I don’t know if they [will be able] to travel. You know, there are some restrictions. But, yeah, we’re going to have a show in Miami (Florida, USA) and in Italy next year.

K+C — It sounds like you’ve got a lot planned!

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. When you’re an artist, there’s a lot [that] keeps on coming. You need to push and push and push.

K+C — What excites you most about this new series?

So, when I had Covid-19 [earlier this year], everything was like vanishing [from] my mind. I was thinking about the work and I was asking myself if I’m no longer here, is this all I can do?

That’s the question I was asking myself each and every day, and I challenged myself when I got up [out of bed]. I want to do more. I want people to see my work. There’s a message. There’s something I want to say and there’s also more I can do. So, since that day, I’ve been here at the studio every day. Pushing, and some new doors are opening, also. People are responding well, so it’s nice. I’m surprised.

K+C — You’re surprised?

Yeah, I’m surprised, but I think I still have a message. I slept more in my practice [in the past]. But, I still have more things I still want to do and apply to the work.

But people are already enjoying the work. The response is amazing about the way I want to push. I still have more time until the end of the year, and I’ve got other [ideas, so] I’m going to order some canvases for another bulk of work or so.

K+C — That’s wonderful! You said that while you were sick, the new series was going through your mind a lot and you really wanted to bring something specific to it. Did you have a different plan before you got sick?

It was not like a different plan. I think I just felt more relaxed.

K+C — Okay, I understand.

People can identify my work now. But I didn’t open myself outside there. I can do more; I can still put more energy into it and make it stronger. I was just too relaxed [before], and I was not happy with the work I was seeing. When I scrolled through my phone when I was sick, I was not happy with the work. So, I said: “Hey, I can do more. I can put more quality [work], I can [put in] more effort. I can tell more stories about this work.”

Now, the sky is the limit. I want to push more. And what? I think in two months, we produced more than 27 pieces. So, yeah. I was hungry.

K+C — That’s a lot of work in a short time! What does that look like on a day-to-day basis? How long were you painting?

I was here at [the studio at] seven in the morning until [about] eight o’clock at night.

K+C — How do your hands handle it?

Ah, as I’m speaking to you now, I don’t feel anything. I feel like I still have more.

For me, I was sick and in quarantine for 14 days. The first week was hard for me, but the second week, like, I wanted to go. I wanted to go and work. But some stuff was still stopping me. I didn’t have power. But, I said I wanna go. I didn’t even have the power to drive. So, for me, I realized I wasted too much time, man. I needed to be out there.

This is my world, man. I need to conquer it. There’s a lot I want to do, so, for me, the Covid woke me up. It’s like someone smacked me and said, “Wake up!”

So I still want to work more. If I get another chance, I still want to produce more of what I do.

It’s been amazing. The journey has been amazing and good things are coming. And you know, what I wished for when I was young is coming now. The puzzle pieces are coming and falling into place. So, we’ll see what next year is gonna give us, but I’m ready. I’m ready.

K+C — That’s amazing. I’m really excited for you!

Yeah, thank you so much. It’s amazing. It’s amazing what I’ve achieved in just one year. I mean, it was amazing, yeah.

K+C — Absolutely. I remember when I reached out to you — it was May of this year, I think. You had just finished one series and you were about to start this one.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

K+C — Now, it’s September. So when you say, “Yeah, I was hungry,” I believe it.

Yeah yeah. I don’t know where I got this energy, but yeah, I was hungry.

K+C — Yeah, that’s brilliant! Well, Tafadzwa, it was amazing to speak with you about your work. Thank you so much for sharing your story. I cannot wait to see what’s to come in the future.

Yeah, thank you so much. It was a pleasure.